|

Reproduced from a paper I wrote for Michael Greer's 'Technology of the Book' course at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock in Fall 2018. Consider yourself standing in a library - you’re sure to have little trouble visualizing the scene. The organization of the shelves, the volumes lined up all the way down the rows, titled along their spines for fingers and eyes to pass over… this setting is nearly as iconic as the book itself. In the infancy of the book as we know it, however, libraries were not nearly so orderly. Massive vellum tomes bore metal knobs and latches to keep them closed and protected as they lay flat across their faces, chained to their shelves, oftentimes too heavy to move. The Renaissance poet Petrarch is known to have nearly lost his legs after dropping a volume of his own inscription on them as he pulled it from the shelf (Brassington 94, Cundall 9). From its birth in the 4th century, the flat-form book endured 1200 years of bondage before finally assuming the noble, upright stance we take for granted today. The Prone TomeFor more than 1,000 years between the invention of the flat-form book in the 4th century and the establishment of the printing press in the 15th, virtually all recorded texts were religious in nature and were confined to an audience of the monasteries, monarchies, and the occasional hyper-wealthy private bibliophile. In this context, portability wasn’t of much concern. Large manuscripts, inscribed on vellum and cased between heavy wooden boards covered with leather, were often laid open on lecterns and desks for study and were not expected to move. Churches and monasteries were furnished with sloped and even revolving desks to make these giant volumes as accessible as possible. Adding to their weight, bosses and corner-caps made of metal, wood, or bone punctuated the covers of these books, as Diehl explains, ‘for the twofold purpose of decoration and keeping the leather from being scratched or harmed as the book lay on its side’ (17). The weight of the heavy wooden cover boards, in addition to metal clasps and latches, was necessary to keep the vellum folios of these great bindings from curling or ‘yawning’ over time (Diehl 17).

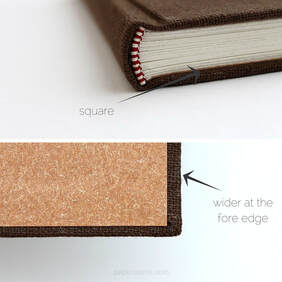

As confused and chaotic a picture as this paints, understanding the limited audience and function of books and libraries during the medieval era justifies the form: heavy religious texts were built to last and organized for their protection and reference by monks and the very few outside the church who could read them. As this audience began to change, so the form and function of the book did as well. The Ascent of Man-uscriptsAccording to Cundall, weight was the major limiting factor for the development of books up through the first half of the 15th century (9). Even if it had been attempted, medieval bindings were liable to collapse under their own weight when stood upright on the shelves. This weight also led the binding edge of manuscripts, which were glued up flat and flush with the cover boards, to split and cave, leaving the spine sunken and unsuitable for displaying the title of a volume. Weihs notes that, at that time, spines were considered the ‘unsightly hinge’ of a book and were usually left undecorated (12).

By the 1540s, the concept of spine-titling and vertical storage had been well-established, presses had been pumping out printed texts for nearly a century, and these cheaper, lighter bindings slowly shed their metal furniture and chains as bookbinders turned their attention to decoration, craftsmanship, and volume to serve their blossoming consumer-base (Brooker xxvi). By the end of that century, these ideas were adopted by the rest of Europe, and what is largely considered the golden age of bookbinding as an art had begun. Bound for Greatness

Works CitedBarbara Durrfeld, Eike. “Terra Incognita: Toward a Historiography of Book Fastenings and Book Furniture.” Book History, vol. 3, 2000, https://0-muse-jhu-edu.librrary.ualr.edu/article/3600 Brassington, W. Salt. A History of the Art of Bookbinding: with Some Account of the Books of the Ancients. Eliot Stock, London, 1894, Google Books https://books.google.com/books/about/A_History_of_the_Art_of_Bookbinding.html?id=jsw5AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false Brooker, Thomas Kimball. “Upright works: The emergence of the vertical library in the 16th century.” 1996, Proquest https://0-search-proquest-com.library.ualr.edu/docview/304278572/fulltextPDF/B598963E94674D60PQ/27?accountid=14482 Cundall, Joseph. On Bookbindings: Ancient and Modern. G. Bell and Sons, 1881, Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=_LRCAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. Dover Publications, Inc., 1980 Weihs, Jean. “A Brief History of Shelving.” Technicalities; Prairie Village, vol. 29, iss. 2, March/April 2009, Proquest https://0-search-proquest-com.library.ualr.edu/libraryscience/docview/195041497/F958572E551B4C60PQ/2?accountid=14482

1 Comment

|